April 1995

By John Irwin

|

Imagine how you would feel if you were handed a 770 A.D. Buddhist prayer manuscript from the era of the earliest Japanese papermaking and writing and the beginnings of Japanese libraries. Such was my experience at Osaka's Prefectural Nakanoshima Library, a venerable 1904 Carnegiesque building also from another era. My eyes widened and I was in euphoria as its urn container was taken off the shelf, the long narrow document in mint condition was unrolled and presented to me. Such surprises and delights were a daily occurrence on my trip to Japan.

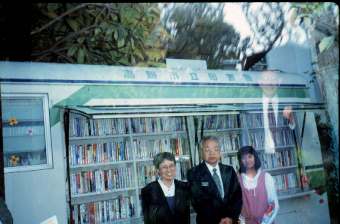

Reading all the books about Japan from the Flagstaff library shelves, listening to Japanese language tapes and frequent replayings of Madame Butterfly did not prepare me for the exhilarating and exhausting two and a half weeks of my visit. Compared to the throbbing mega cities of Osaka and Tokyo, metro Phoenix and Tucson seem like small, quiet burgs. The contrast between my life in the solitary Coconino forest and this intense urban experience made the venture even more remarkable. Since library school I have been interested in the "Big Picture," the panorama of Knowledge in its totality- how it is created and organized, and the uses it is put to. My respect for scholarship is longstanding, and I have been fascinated with how epistemology is palpably translated into cultural terms, which eventually become the backbone of civilization. As custodians of this knowledge, we librarians are in the "civilization" business. It was extremely exciting for me to have the opportunity to investigate the recorded knowledge of such as ancient and complex society, so different from our own. Certainly I felt as if I were both a scholar adventurer and info hound as I dashed through fifteen public and academic libraries, the National Diet Library and the National Archives, absorbing and noting all that I could in such a brief time. My two stated purposes were to examine rare books and manuscripts and learn how they are cared for, and to investigate the status of library automation. Always wearing specially provided sandals (for cleanliness) I was escorted through floors and floors of closed areas in libraries which contained vast amounts of manuscripts and codexes representing seventeen centuries of knowledge. At the National Diet Library I was even taken to a vault within a vault far underground, to see the rarest and most precious literary and art treasures in Japan. How dazzling, for example, were the illuminated scrolls and the secular and sensual ukiyo-e woodblock printings from the Edo Period. At the National Archives I was astounded when Hirohito's royal manuscript caskets were opened for me right there in the stacks and I viewed official documents of the Empire. Knowing that many of the items have never been reproduced, I well understood that such a privilege of access given to me was one that most Japanese will never have. At the Osaka City University Library I was equally surprized when I was escorted to five stacks levels of rare Seventeenth through Nineteenth Century books and pamphlets, primarily European, relating to economics. It was pointed out that this was probably one of the the three largest collections in the world of the history of economics, hundreds of thousands of titles. Impressive! (The collection survived the WWII bombings, but 70,000 volumes were destroyed by falling off trucks in the middle of the night. At the beginning of the American occupation it was decreed that the library was to be a hospital, and the entire collection had to be moved within a few hours. The reading room became a GI dance hall!). In the area of automation, I discovered that many libraries wer scrambling to convert card catalogs to OPACs (an acronym understood by all Japanese librarias) if they had not done so already. Many libraries had access to a Japanese periodical index and national bibliography on CD. However, online access to DIALOG and the Internet seemed much more limited to only some of the academic librarians. At the National Diet Library I witnessed the preparation of JAPANMARC records on huge keyboards using Japanese Kanji characters. There I also discussed with the Chief of the Automation Division the plans for a massive fiber optic cabling of the library. My delight in the collections of these libraries was subsumed, however, by my appreciation of the extraordinary cordiality and friendliness shown to me by dozens of librarians I met. The red carpet was rolled out. Never before in my travels have I been shown such respect and honor. I was pampered and treated as if I was the Librarian of Congress or some VIP. For instance, a librarian and a government car whose driver wore white gloves were waiting at the Naitonal Diet Library to escort me to and from the National Archives. Their courtesy also extended beyond their libraries. I was royally wined and dined. One day I was taken to a traditional Japanese restaurant (in a mansion of the Sumitomo Family) by librarians from the Yuhigaoka Prefectural Library. We sat on the floor in a small room with a view of the cherry trees in full blossom, and were served course after course of exquisite delicacies by a geisha. A Friday invitation by librarians included dinner, being taken to a karaoke club and a stroll through the glittering night life of Osaka. A part of my function was to be that of a library diplomat, establishing closer ties between libraries of Arizona and Japan, bridging our two cultures. At each library I was formally received and made a presentation of an Arizona gift- a Friends of the Flagstaff Library bookbag containing an AzLA Newsletter, an issue of American Libraries, a Grand Canyon book in Japanese and other library material. In a land where people worship mountains, there was much admiraton for photos of our San Francisco Peaks. There was equal interst in the Arizona Highways map of Arizona and the photos with which I showcased the buildings and services of the Flagstaff Public Library and the Northern Arizona University Cline Library. In Toyko I had the privilege to meet with Mr. Kurihara, the Chairman of the Board of Directors, and three other officials of the Japan Library Association. We spent a morning discussing librarianship in our two countries, international cooperation and the upcoming IFLA (International Federation of Library Associations) conference in Istanbul. Afterwards they escorted me to an exclusive restaurant at the International House, a center for scholars visiting from other countries.

This tour offered many impressions of Japanese libraries. The striking architecture and decoration of some of the recent buildings especially gave me new ideas. Near Kolbe, the Mukogawa Women's University Library is one of the most successful library buildings I have ever seen. Fortunately earthquake damage to it was minimal. Although there are many similiarities between our libraries, there are also descrepancies, reflecting our different societies. I was repeatedly told, for instance, that academic library directors are frequently chosen form the ranks of senior faculty and scholars. These people have sometimes little experience in managing the complex operations of a large library. It was surprising to learn that in some public libraries the classification "librarian" meant that one person might interchangeably do reference, checkout, book retrieval from storage and paging. Many libraries had closed stack areas, and the Tokyo Metropolitan Central Public Library, a collection of a million and a half volumes, was entirely non-circulating. The quiet habits of Japanese users in all libraries were noteworthy, and I was told of seating problems caused by scholarly high school students silently cramming for their all-important tests which determine their future. My accounts of our Wild West libraries in Flagstaff and Arizona where problem patrons are the order of the day seemed shocking in Japan. Japanese civility and politeness are almost a national pastime, the crime rate is low and women can even safely walk on the street at night. My three host families, the Torikatas, the Yamabes and the Takanos outdid themselves in providing for my comfort. It was very enjoyable making friends with these people, all of whom had once lived in the United States, and seeing Japanese life from the inside. Witnessing the refinements of Japanese behavior and lifestyles was a great pleasure. It was charming to sleep on the floor on a futon in rooms with paper walls, walking in sandals, strolling in exquisite Japanese gardens and continually being served elaborate and delicious meals of unusual food, such as squid ink muffins and raw jellyfish. The families escorted me to several dozen Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines at Kamakura and the ancient capitals of Nara and Kyoto. Long having an interest in Asian values and being a Yoga devotee, these holy places affected me deeply. The stuning bright saffron of the monks' robes and the image of the torii gates outside Shinto shrines are now permanently emblazoned on my retina. These places were a direct link to the ancient manuscripts I had been viewing. In particular, Kyoto seemed to me as one of the world's great cities with its many museums, gardens and shrines. I would be remiss if I did not thank those who made my trip such a smooth experience. Here in Arizona, Kris Swank, Carol Elliott and Shizuko Radbill made arrangments and volunteered helpful suggestions. Professor Tsutomu Shihota of St. Andrews University in Osaka took large blocks of time off from his teaching and writing schedule, and become my personal tour guide. Having just gotten into my stride, I did not want to leave when my trip drew to a close. Culture shock was waiting for me upon returning to America. I look forward to the time when I can return to this remarkable country to renew friendships and do more exploring. I also look forward to visits by some of the Japanese librarians who were excited with my invitation to tour Arizona libraries. Gazing at the endless blue of the Pacific on my return flight, I mused over the paradoxes of life. In the Spring of 1945 the ocean was a furious battlefield between our two countries. My father participated in WWII. Now exactly fifty years later his son was sent to Japan on a mission of peace and goodwill. I am struck that libraries are the reason for my trip: they are champions of pacific values, promoting comprehension and understanding, a reasonable alternative to the evils of war. There are few experiences more "educational" than travel. Only by visiting other countries and cultures can we begin to make sense of our own. To my knowledge the Horner Fellowship is unique to American librarianship, and it is certainly a boon for AzLA and its members. Ties between our libraries are strengthened with each Horner visit, and there is much that we have to learn from each other. I hope that in the future all AzlA members will consider applying for the fellowship to become a part of this splendid international experience. For me this trip to Japan has certainly been a highlight of my career. I learned much, and from it I will have vivid memories and lifelong friends. |